We stand on the brink of a technological revolution that will fundamentally alter the way we live, work, and relate to one another. In its scale, scope, and complexity, the transformation will be unlike anything humankind has experienced before. We do not yet know just how it will unfold, but one thing is clear: the response to it must be integrated and comprehensive, involving all stakeholders of the global polity, from the public and private sectors to academia and civil society.

The First Industrial Revolution used water and steam power to mechanize production. The Second used electric power to create mass production. The Third used electronics and information technology to automate production. Now a Fourth Industrial Revolution is building on the Third, the digital revolution that has been occurring since the middle of the last century. It is characterized by a fusion of technologies that is blurring the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres.

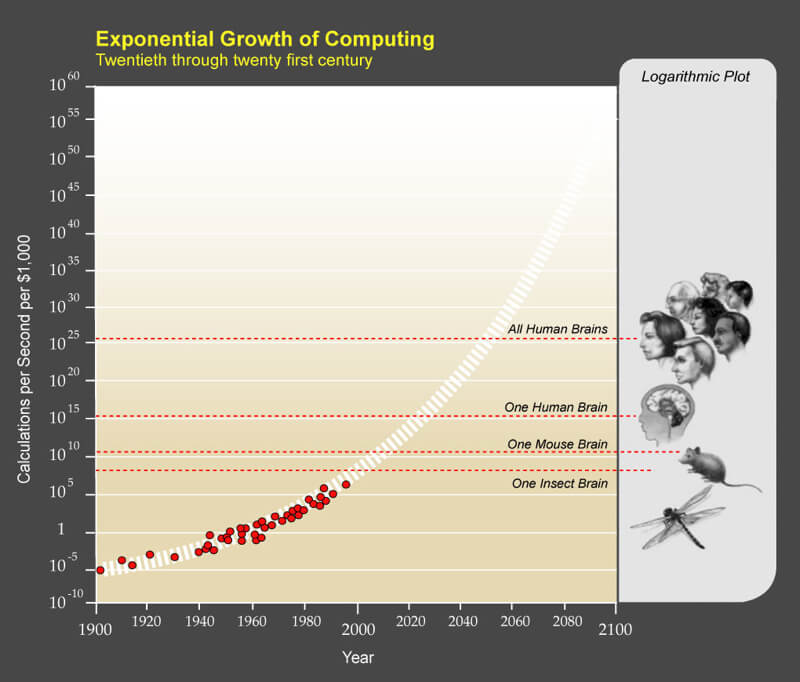

There are three reasons why today’s transformations represent not merely a prolongation of the Third Industrial Revolution but rather the arrival of a Fourth and distinct one: velocity, scope, and systems impact. The speed of current breakthroughs has no historical precedent. When compared with previous industrial revolutions, the Fourth is evolving at an exponential rather than a linear pace. Moreover, it is disrupting almost every industry in every country. And the breadth and depth of these changes herald the transformation of entire systems of production, management, and governance.

The possibilities of billions of people connected by mobile devices, with unprecedented processing power, storage capacity, and access to knowledge, are unlimited. And these possibilities will be multiplied by emerging technology breakthroughs in fields such as artificial intelligence, robotics, the Internet of Things, autonomous vehicles, 3-D printing, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science, energy storage, and quantum computing.

Already, artificial intelligence is all around us, from self-driving cars and drones to virtual assistants and software that translate or invest. Impressive progress has been made in AI in recent years, driven by exponential increases in computing power and by the availability of vast amounts of data, from software used to discover new drugs to algorithms used to predict our cultural interests. Digital fabrication technologies, meanwhile, are interacting with the biological world on a daily basis. Engineers, designers, and architects are combining computational design, additive manufacturing, materials engineering, and synthetic biology to pioneer a symbiosis between microorganisms, our bodies, the products we consume, and even the buildings we inhabit.

Challenges and opportunities

Like the revolutions that preceded it, the Fourth Industrial Revolution has the potential to raise global income levels and improve the quality of life for populations around the world. To date, those who have gained the most from it have been consumers able to afford and access the digital world; technology has made possible new products and services that increase the efficiency and pleasure of our personal lives. Ordering a cab, booking a flight, buying a product, making a payment, listening to music, watching a film, or playing a game—any of these can now be done remotely.

In the future, technological innovation will also lead to a supply-side miracle, with long-term gains in efficiency and productivity. Transportation and communication costs will drop, logistics and global supply chains will become more effective, and the cost of trade will diminish, all of which will open new markets and drive economic growth.

At the same time, as the economists Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee have pointed out, the revolution could yield greater inequality, particularly in its potential to disrupt labor markets. As automation substitutes for labor across the entire economy, the net displacement of workers by machines might exacerbate the gap between returns to capital and returns to labor. On the other hand, it is also possible that the displacement of workers by technology will, in aggregate, result in a net increase in safe and rewarding jobs.

We cannot foresee at this point which scenario is likely to emerge, and history suggests that the outcome is likely to be some combination of the two. However, I am convinced of one thing—that in the future, talent, more than capital, will represent the critical factor of production. This will give rise to a job market increasingly segregated into “low-skill/low-pay” and “high-skill/high-pay” segments, which in turn will lead to an increase in social tensions.

In addition to being a key economic concern, inequality represents the greatest societal concern associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The largest beneficiaries of innovation tend to be the providers of intellectual and physical capital—the innovators, shareholders, and investors—which explains the rising gap in wealth between those dependent on capital versus labor. Technology is therefore one of the main reasons why incomes have stagnated, or even decreased, for a majority of the population in high-income countries: the demand for highly skilled workers has increased while the demand for workers with less education and lower skills has decreased. The result is a job market with a strong demand at the high and low ends, but a hollowing out of the middle.

This helps explain why so many workers are disillusioned and fearful that their own real incomes and those of their children will continue to stagnate. It also helps explain why middle classes around the world are increasingly experiencing a pervasive sense of dissatisfaction and unfairness. A winner-takes-all economy that offers only limited access to the middle class is a recipe for democratic malaise and dereliction.

Discontent can also be fueled by the pervasiveness of digital technologies and the dynamics of information sharing typified by social media. More than 30 percent of the global population now uses social media platforms to connect, learn, and share information. In an ideal world, these interactions would provide an opportunity for cross-cultural understanding and cohesion. However, they can also create and propagate unrealistic expectations as to what constitutes success for an individual or a group, as well as offer opportunities for extreme ideas and ideologies to spread.

The impact on business

An underlying theme in my conversations with global CEOs and senior business executives is that the acceleration of innovation and the velocity of disruption are hard to comprehend or anticipate and that these drivers constitute a source of constant surprise, even for the best connected and most well informed. Indeed, across all industries, there is clear evidence that the technologies that underpin the Fourth Industrial Revolution are having a major impact on businesses.

On the supply side, many industries are seeing the introduction of new technologies that create entirely new ways of serving existing needs and significantly disrupt existing industry value chains. Disruption is also flowing from agile, innovative competitors who, thanks to access to global digital platforms for research, development, marketing, sales, and distribution, can oust well-established incumbents faster than ever by improving the quality, speed, or price at which value is delivered.

Major shifts on the demand side are also occurring, as growing transparency, consumer engagement, and new patterns of consumer behavior (increasingly built upon access to mobile networks and data) force companies to adapt the way they design, market, and deliver products and services.

A key trend is the development of technology-enabled platforms that combine both demand and supply to disrupt existing industry structures, such as those we see within the “sharing” or “on demand” economy. These technology platforms, rendered easy to use by the smartphone, convene people, assets, and data—thus creating entirely new ways of consuming goods and services in the process. In addition, they lower the barriers for businesses and individuals to create wealth, altering the personal and professional environments of workers. These new platform businesses are rapidly multiplying into many new services, ranging from laundry to shopping, from chores to parking, from massages to travel.

On the whole, there are four main effects that the Fourth Industrial Revolution has on business—on customer expectations, on product enhancement, on collaborative innovation, and on organizational forms. Whether consumers or businesses, customers are increasingly at the epicenter of the economy, which is all about improving how customers are served. Physical products and services, moreover, can now be enhanced with digital capabilities that increase their value. New technologies make assets more durable and resilient, while data and analytics are transforming how they are maintained. A world of customer experiences, data-based services, and asset performance through analytics, meanwhile, requires new forms of collaboration, particularly given the speed at which innovation and disruption are taking place. And the emergence of global platforms and other new business models, finally, means that talent, culture, and organizational forms will have to be rethought.

Overall, the inexorable shift from simple digitization (the Third Industrial Revolution) to innovation based on combinations of technologies (the Fourth Industrial Revolution) is forcing companies to reexamine the way they do business. The bottom line, however, is the same: business leaders and senior executives need to understand their changing environment, challenge the assumptions of their operating teams, and relentlessly and continuously innovate.

The impact on government

As the physical, digital, and biological worlds continue to converge, new technologies and platforms will increasingly enable citizens to engage with governments, voice their opinions, coordinate their efforts, and even circumvent the supervision of public authorities. Simultaneously, governments will gain new technological powers to increase their control over populations, based on pervasive surveillance systems and the ability to control digital infrastructure. On the whole, however, governments will increasingly face pressure to change their current approach to public engagement and policymaking, as their central role of conducting policy diminishes owing to new sources of competition and the redistribution and decentralization of power that new technologies make possible.

Ultimately, the ability of government systems and public authorities to adapt will determine their survival. If they prove capable of embracing a world of disruptive change, subjecting their structures to the levels of transparency and efficiency that will enable them to maintain their competitive edge, they will endure. If they cannot evolve, they will face increasing trouble.

This will be particularly true in the realm of regulation. Current systems of public policy and decision-making evolved alongside the Second Industrial Revolution, when decision-makers had time to study a specific issue and develop the necessary response or appropriate regulatory framework. The whole process was designed to be linear and mechanistic, following a strict “top down” approach.

But such an approach is no longer feasible. Given the Fourth Industrial Revolution’s rapid pace of change and broad impacts, legislators and regulators are being challenged to an unprecedented degree and for the most part are proving unable to cope.

How, then, can they preserve the interest of the consumers and the public at large while continuing to support innovation and technological development? By embracing “agile” governance, just as the private sector has increasingly adopted agile responses to software development and business operations more generally. This means regulators must continuously adapt to a new, fast-changing environment, reinventing themselves so they can truly understand what it is they are regulating. To do so, governments and regulatory agencies will need to collaborate closely with business and civil society.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution will also profoundly impact the nature of national and international security, affecting both the probability and the nature of conflict. The history of warfare and international security is the history of technological innovation, and today is no exception. Modern conflicts involving states are increasingly “hybrid” in nature, combining traditional battlefield techniques with elements previously associated with nonstate actors. The distinction between war and peace, combatant and noncombatant, and even violence and nonviolence (think cyberwarfare) is becoming uncomfortably blurry.

As this process takes place and new technologies such as autonomous or biological weapons become easier to use, individuals and small groups will increasingly join states in being capable of causing mass harm. This new vulnerability will lead to new fears. But at the same time, advances in technology will create the potential to reduce the scale or impact of violence, through the development of new modes of protection, for example, or greater precision in targeting.

The impact on people

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, finally, will change not only what we do but also who we are. It will affect our identity and all the issues associated with it: our sense of privacy, our notions of ownership, our consumption patterns, the time we devote to work and leisure, and how we develop our careers, cultivate our skills, meet people, and nurture relationships. It is already changing our health and leading to a “quantified” self, and sooner than we think it may lead to human augmentation. The list is endless because it is bound only by our imagination.

I am a great enthusiast and early adopter of technology, but sometimes I wonder whether the inexorable integration of technology in our lives could diminish some of our quintessential human capacities, such as compassion and cooperation. Our relationship with our smartphones is a case in point. Constant connection may deprive us of one of life’s most important assets: the time to pause, reflect, and engage in meaningful conversation.

One of the greatest individual challenges posed by new information technologies is privacy. We instinctively understand why it is so essential, yet the tracking and sharing of information about us is a crucial part of the new connectivity. Debates about fundamental issues such as the impact on our inner lives of the loss of control over our data will only intensify in the years ahead. Similarly, the revolutions occurring in biotechnology and AI, which are redefining what it means to be human by pushing back the current thresholds of life span, health, cognition, and capabilities, will compel us to redefine our moral and ethical boundaries.

Shaping the future

Neither technology nor the disruption that comes with it is an exogenous force over which humans have no control. All of us are responsible for guiding its evolution, in the decisions we make on a daily basis as citizens, consumers, and investors. We should thus grasp the opportunity and power we have to shape the Fourth Industrial Revolution and direct it toward a future that reflects our common objectives and values.

To do this, however, we must develop a comprehensive and globally shared view of how technology is affecting our lives and reshaping our economic, social, cultural, and human environments. There has never been a time of greater promise, or one of greater potential peril. Today’s decision-makers, however, are too often trapped in traditional, linear thinking, or too absorbed by the multiple crises demanding their attention, to think strategically about the forces of disruption and innovation shaping our future.

In the end, it all comes down to people and values. We need to shape a future that works for all of us by putting people first and empowering them. In its most pessimistic, dehumanized form, the Fourth Industrial Revolution may indeed have the potential to “robotize” humanity and thus to deprive us of our heart and soul. But as a complement to the best parts of human nature—creativity, empathy, stewardship—it can also lift humanity into a new collective and moral consciousness based on a shared sense of destiny. It is incumbent on us all to make sure the latter prevails